Siegfried has been described as the Scherzo of the Ring cycle. While it certainly has its amusing moments, it also lays the groundwork for the culminating end of the world. This is heralded by Wotan’s recognition of the inevitable and Siegfried’s destruction of his father’s spear, signifying the voiding of the gods’ contract with the other races. These serious implications are well drawn out by Suzanne Chaundy’s production for Melbourne Opera, which also continues to entertain,

The Bendigo Ring continues with the very high standard of singing and acting established in the previous two operas. Andrew Bailey's set continues to impress, the platform with its circular cutout being raised and lowered to create different environments for the three acts. In Act 1, we find ourselves in the incredibly messy kitchen-workshop-junkshop shared by Mime and the young hero, Siegfried. Steps lead up towards the back so that the action takes place on two levels. While Mime potters around at ground level forging and cooking, Siegfried makes his appearance at the top of the stairs; his captured bear is not seen, being tethered to a straining rope which he then turns loose.

In the second act, the platform is lowered, leaving the larger circular cutout visible, filled by the dragon’s scaly skin. The voice of Fafner is first heard offstage and, when roused to anger, his giant eye fills the circle, contracting into an animated dragon’s head. In Act 3, we are returned to the mountain top we left in Die Walküre, surrounded by flames for the second scene. “Das ist kein Mann!” is milked for its obvious laugh (I have seen this fall flat), before the love duet gets properly under way.

The propulsive thrust of the orchestra was maintained under Anthony Negus, albeit with some unfortunate violin mishaps in the third act. Otherwise, the orchestra did its job well, and the melodious harps stationed on the extreme ends of the stage rippled forth. The singers continued to develop their characters, Robert Macfarlane entertaining as the slimy yet pathetic Mime, singing with accurate but somewhat bleating tone appropriate to his characterisation.

Warwick Fyfe's commanding yet thoughtful Wotan, now in Wanderer mode, sang even more strongly, if anything, with rich, resonant tone. Simon Meadows’ Alberich maintained his singing chops and sleazy persona, and Steven Gallop’s Fafner, now in dragon guise, sang convincingly from off stage. Deborah Humble returned as Erda, in gleaming white this time, with multiple copies of her face projected above, as against the single one in Rheingold. She sang with even greater warmth and authority here. Up-and-coming soprano Rebecca Rashleigh was a delightful Woodbird, fittingly attired in a green gown, projecting sweetly.

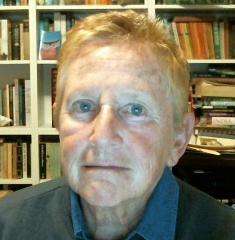

As Siegfried, Bradley Daley was the other newcomer to the cycle, the central pivot of this opera. He impressed with ringing effortless Heldentenor tone and portrayed the fearless young (if not very bright, cf. Anna Russell) hero with unflagging energy and commitment. He was well-matched by Antoinette Halloran’s Brünnhilde in this regard, though one might have wished for a somewhat narrower vibrato to her voice. Nonetheless the concluding love scene was all it should be, culminating in ecstatic exhilaration.